Imagine!

A frightened child sits beside you, her hand clasped tightly in yours. Silent tears stream down her face, clouding her otherwise golden brown eyes with a pool of grey. She is voiceless. Despite her heartbreaking pleas, you cannot help her. She must go.

Sitting on the damp bench, you wrap your arm around her quivering body and wince as you look at her grief-stricken face – the same sweet face that  nourished your soul for the past six years. Images of her inundate your mind, cascading from one scene to another. The day she was born was your happiest ever. You planted a tree in her honour that year. Will it continue to grow in her absence? You recall how easy it was to soothe her then. You’d hold her in your arms and sing sweet lullabies, the very ones your mother once sang to you. But who will comfort her now when she’s lonely and scared? Will they care for her when she is unhappy or sick? What if she’s hurt? What if she’s hungry? You panic. You try to restrain the fear that is taking over.

nourished your soul for the past six years. Images of her inundate your mind, cascading from one scene to another. The day she was born was your happiest ever. You planted a tree in her honour that year. Will it continue to grow in her absence? You recall how easy it was to soothe her then. You’d hold her in your arms and sing sweet lullabies, the very ones your mother once sang to you. But who will comfort her now when she’s lonely and scared? Will they care for her when she is unhappy or sick? What if she’s hurt? What if she’s hungry? You panic. You try to restrain the fear that is taking over.

You close your eyes and pray. Please take care of my baby. Oh hush, you mustn’t let her see you cry, or she will surely realize your comforting words were nothing but lies.

It will not be alright when they tell her she must abandon her birth name. It will not be alright when they cut off her braids. It will not be alright when she feels homesick and is denied her brother’s embrace. It will not be alright when she wonders why you cannot be there on her birthday or why she has to miss grandpa’s 70th. Time will surely not fly. But you do and say what you must, for the choice is not yours.

It will not be alright when they tell her she must abandon her birth name. It will not be alright when they cut off her braids. It will not be alright when she feels homesick and is denied her brother’s embrace. It will not be alright when she wonders why you cannot be there on her birthday or why she has to miss grandpa’s 70th. Time will surely not fly. But you do and say what you must, for the choice is not yours.

The cruel rain continues. They will come for her and you must let her go. You gave birth to her but somehow you do not know what is best for her. You raised her, nourished her, taught her, but she is not yours.

A van emerges from around the hills, slowly making its way up the road. She squeezes your hand, a final plea. I n just a few moments the scent of your hands will be all she has left of you.

n just a few moments the scent of your hands will be all she has left of you.

“Please Mommy, I don’t want to go”.

A kiss, a hug and a swift smell of her hair, your heart is in pieces, yet you pry her hands out of yours. You try to sound sensible when you know nothing you say or do will ever be so.

“I will see you in the summer, my sweet rose,” agony overwhelms you as you watch her climb aboard, sobbing and confused. Why is mommy letting this happen? What did I do wrong? Doesn’t she love me anymore?

You are numb. You wave when all you want to do is shout at the world. That is my baby disappearing into the thick mist.

You are numb. You wave when all you want to do is shout at the world. That is my baby disappearing into the thick mist.

You continue to stare long after the van disappears behind the hills. Surely this must be a horrible dream, a nightmare.

You look around. All is still. You pick up the discarded doll and hold it close to your body. You weep for the child they thieved from your home.

Imagine!

Lora Rozler

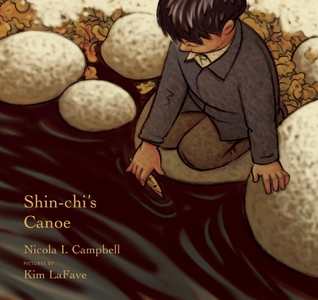

It was a few months ago that my friend and colleague, Michele Parkin, enlightened me with one of her picture books, Shin-Chi’s Canoe by Nicola Campbell. I had reached out to her a few days prior when I sought an Ojibway translation for a picture book I was working on at the time. As always, she was more than happy to help and the discussion that ensued left me wanting to learn more about the Aboriginal people’s struggles. Knowing my passion for children’s literature, Michele kindly offered her book.

I brought the book home with me the same day and as I read it, a sense of rage began to build. My children happened to be playing in a nearby room and and all I remember feeling is deep sadness for those families whose children were taken away from them, stolen from their home, their culture, their life. There was something about the the way the story was told that touched me deeply. As a mother, the thought of having to endure something so horrific is beyond comprehension.

I’d like to share an article I read online, written by Erin Hanson, a researcher at The University of British Columbia. It beautifully articulates and captures the effects of the Residential school experience on the Indigenous people. You can visit the article by clicking the image below:

Here is a collection of compelling picture books that shed further light into this travesty, including the one that started me on this journey. Poignant and informative, they are the perfect springboard to a great discussion with our students.

Shin-chi’s Canoe

Shin-chi’s Canoe

Nicola I. Campbell, Kim LaFave (Illustrator)

Groundwood Books

When they arrive at school, Shi-shi-etko reminds Shinchi, her six-year-old brother, that they can only use their English names and that they can’t speak to each other. For Shinchi, life becomes an endless cycle of church mass, school, and work, punctuated by skimpy meals. He finds solace at the river, clutching a tiny cedar canoe, a gift from his father, and dreaming of the day when the salmon return to the river — a sign that it’s almost time to return home. This poignant story about a devastating chapter in First Nations history is told at a child’s level of understanding.

Shi-shi-etko

Shi-shi-etko

Nicola I. Campbell , Kim LaFave (Illustrator)

Groundwood Books

In just four days young Shi-shi-etko will have to leave her family and all that she knows to attend residential school.

She spends her last days at home treasuring the beauty of her world — the dancing sunlight, the tall grass, each shiny rock, the tadpoles in the creek, her grandfather’s paddle song. Her mother, father and grandmother, each in turn, share valuable teachings that they want her to remember. And so Shi-shi-etko carefully gathers her memories for safekeeping.

Richly hued illustrations complement this gently moving and poetic account of a child who finds solace all around her, even though she is on the verge of great loss — a loss that native people have endured for generations because of the residential schools system.

When I Was Eight

Christy Jordan-Fenton, Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, Gabrielle Grimard (Illustrations)

Annick Press

“Nothing will stop a strong-minded young Inuit girl from learning how to read.”

Olemaun is eight and knows a lot of things. But she does not know how to read. She must travel to the outsiders’ school to learn, ignoring her father’s warning of what will happen there.

The nuns at the school take her Inuit name and call her Margaret. They cut off her long hair and force her to do chores. She has only one thing left — a book about a girl named Alice, who falls down a rabbit hole.

Margaret’s tenacious character draws the attention of a black-cloaked nun who tries to break her spirit at every turn. But she is more determined than ever to read.

By the end, Margaret knows that, like Alice, she has traveled to a faraway land and stood against a tyrant, proving herself to be brave and clever.

Based on the true story of Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, and complemented by stunning illustrations, “When I Was Eight” makes the bestselling “Fatty Legs” accessible to young children. Now they, too, can meet this remarkable girl who reminds us what power we hold when we can read.

Not My Girl

Christy Jordan-Fenton, Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, Gabrielle Grimard (Illustrations)

Annick Press

“When I Was Eight” was called “utterly compelling” by “Kirkus”in a starred review.

“Margaret can’t wait to see her family, but her homecoming is not what she expected.”

Two years ago, Margaret left her Arctic home for the outsiders’ school. Now she has returned and can barely contain her excitement as she rushes towards her waiting family — but her mother stands still as a stone. This strange, skinny child, with her hair cropped short, can’t be her daughter. “Not my girl!” she says angrily.

Margaret’s years at school have changed her. Now ten years old, she has forgotten her language and the skills to hunt and fish. She can’t even stomach her mother’s food. Her only comfort is in the books she learned to read at school.

Gradually, Margaret relearns the words and ways of her people. With time, she earns her father’s trust enough to be given a dogsled of her own. As her family watches with pride, Margaret knows she has found her place once more.

Based on the true story of Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, and complemented by evocative illustrations, “Not My Girl” makes the original, award-winning memoir, “A Stranger at Home,” accessible to younger children. It is also a sequel to the picture book “When I Was Eight.” A poignant story of a determined young girl’s struggle to belong, it will both move and inspire readers everywhere.

A Stranger at Home

Christy Jordan-Fenton, Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, Liz Amini-Holmes (Illustrator)

Annick Press

“The powerful memoir of an Inuvialuit girl searching for her true self when she returns from residential school.”

Traveling to be reunited with her family in the Arctic, 10-year-old Margaret Pokiak can hardly contain her excitement. It’s been two years since her parents delivered her to the school run by the dark-cloaked nuns and brothers.

Coming ashore, Margaret spots her family, but her mother barely recognizes her, screaming, “Not my girl.” Margaret realizes she is now marked as an outsider.

And Margaret is an outsider: she has forgotten the language and stories of her people, and she can’t even stomach the food her mother prepares.

However, Margaret gradually relearns her language and her family’s way of living. Along the way, she discovers how important it is to remain true to the ways of her people — and to herself.

Highlighted by archival photos and striking artwork, this first-person account of a young girl’s struggle to find her place will inspire young readers to ask what it means to belong.

Fatty Legs

Christy Jordan-Fenton, Margaret Pokiak-Fenton, Liz Amini-Holmes (Illustrator)

Annick Press

The moving memoir of an Inuit girl who emerges from a residential school with her spirit intact.

Eight-year-old Margaret Pokiak has set her sights on learning to read, even though it means leaving her village in the high Arctic. Faced with unceasing pressure, her father finally agrees to let her make the five-day journey to attend school, but he warns Margaret of the terrors of residential schools.

At school Margaret soon encounters the Raven, a black-cloaked nun with a hooked nose and bony fingers that resemble claws. She immediately dislikes the strong-willed young Margaret. Intending to humiliate her, the heartless Raven gives gray stockings to all the girls — all except Margaret, who gets red ones. In an instant Margaret is the laughingstock of the entire school.

In the face of such cruelty, Margaret refuses to be intimidated and bravely gets rid of the stockings. Although a sympathetic nun stands up for Margaret, in the end it is this brave young girl who gives the Raven a lesson in the power of human dignity.

Complemented by archival photos from Margaret Pokiak-Fenton’s collection and striking artwork from Liz Amini-Holmes, this inspiring first-person account of a plucky girl’s determination to confront her tormentor will linger with young readers.

For Further Reading

Where are the Children? Healing the Legacy of Residential Schools http://www.wherearethechildren.ca/

Canadian Broadcast Commission. Truth and Reconciliation: Stolen Children. This site contains FAQ on residential schools and compensation here.

Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. “Indian Residential Schools.”

Aboriginal Healing Foundation – www.ahf.ca

The Indian Residential School Survivors Society – http://www.irsss.ca/

Legacy of Hope – http://www.legacyofhope.ca/Home.aspx

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada – www.trc.ca

Commission of Canada – www.trc.ca

If you live in Canada, here are some events coming up in Toronto:

If you live in Canada, here are some events coming up in Toronto:

On Wednesday, May 20 at 7 p.m. at St. Matthew’s Church, (Bloor St.), Bishop Mark MacDonald, National Indigenous Bishop of the Anglican Church, will speak on the Doctrine of Discovery by which the Christian Church took control of non-European lands and how it is possible to achieve Reconciliation.

On Sunday, May 31st between 2 – 3 p.m. there will be a Reconciliation Walk (starting at Council Fire Native Cultural Centre at 439 Dundas Street East, along Dundas north on University to Queen’s Park), in show of solidarity with the final gathering for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

On Tuesday, June 2nd between 9:30-12:00, there will be a vigil at Church of the Redeemer (Bloor and Avenue), as hundreds of people arrive in Ottawa by train, bus and on foot from all over Canada, to hear the Commissioners Report. Visit KAIROS Canada for information.

On Saturday, June 6th at 10 a.m. St. Philip’s Church (Etobicoke) will hold Aboriginal Running’s Annual Walk/Run along the Humber River, the traditional Carrying Place of the Mississauga Nation. There will be a gathering afterwards in the Parish Hall.

On Sunday, June 7th at 10:30 a.m. at St. Philip’s Anglican Church(Etobicoke), there will be an Aboriginal Service to celebrate and pray for renewal in the lives of the Indigenous People who live in Canada and their relationships with the settler peoples of Canada.

![]() Toronto and Etobicoke sit on the traditional territory of the Mississauga Anishinabe and continues to be home to people of many Indigenous Nations.

Toronto and Etobicoke sit on the traditional territory of the Mississauga Anishinabe and continues to be home to people of many Indigenous Nations.

![]() Sometimes inspiration comes to us from experiences we have, movies we watch or lectures we hear. Other times we are most inspired by what touches our heart, as with me, a simple picture book, a book that dove into something quite complex. Though not always pleasant, these stories give us insight into the world we live in – the good, the bad, and every shade in between.

Sometimes inspiration comes to us from experiences we have, movies we watch or lectures we hear. Other times we are most inspired by what touches our heart, as with me, a simple picture book, a book that dove into something quite complex. Though not always pleasant, these stories give us insight into the world we live in – the good, the bad, and every shade in between.

Childhood Thieves is the first in a series we will be featuring under our new article collection aptly named World on a Limb. Please feel free to contact us if you have a story you wish to share and possibly feature with us (please include World on a Limb in the subject line). | wordsonalimb@bell.net

Lora

Thank you so much for sharing this. It is heartbreaking and the stories need to be told. The books are a real eye opener and told in such a great way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The stories are quite remarkable. They capture so much in a delicate and touching way. (I certainly plan on adding them to my personal library collection).

Though this was not an easy subject to broach, I felt compelled to share it.

Thank you, Jessie, for taking the time to read the article and for your feedback.

LikeLike

Every culture in the world has something good to offer humanity and to enrich human lives. When a child is weaned away from his roots, and a people from their way of life, the world loses the accumulated wisdom of generations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully said! That ‘variety’ is in deed what needs to be nurtured and celebrated. Every horrible period in history was (and still is) rooted in not seeing THAT philosophy. Thank you for your feedback Gita. 🙂

LikeLike